The Mast Beast

Corwen ap Broch

(originally written for Pagan Dawn magazine)

Introduction

Dressing up as and impersonating the movements of animals is a primal activity that all human societies seem to indulge in. Our old friend the Trois Freres Sorcerer (a cave painting from France dated to around 13,000 BC) shows that our ancient ancestors in Europe dressed in the skins of animals and danced, probably as part of

religious or magical rituals. We haven't changed much since. This article explores the history and more importantly the construction and uses of one particular sub-type of animal disguise, the Mast Beast.

Oosers, Tourney Horses and Mast Beasts

There are many traditional ways to disguise yourself as an animal, the most obvious of which is to wear a mask. There are various masked animal guisers in European tradition, perhaps the most dramatic of which was the Dorset Ooser1, a heavy wooden horned head with a fierce bull like face. However a mask only transforms the face of its wearer, and whilst this may engender a similar psychic shift in performer and audience, people have striven for more dramatic physical transformations.

One can wear a cloth covered frame, traditionally of wickerwork, which totally covers the wearer making him seem entirely the impersonated beast. Such was the case with the Norwich Dragon, Snap2, whose costume at times even included flame throwing machines and fireworks. No wonder the operator had to be paid danger money! If however the upper body of the wearer is allowed to project through the top of the frame, the body of the beast can be made to resemble an animal which the operator is riding. False legs may be hung from the sides to add to the effect, and the model head of the beast projecting out in front can be animated with stiff mock reins, or even feature opening and closing jaws. This is the familiar Hobby Horse of medieval times, still in use as part of the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance3 among others, and is classified by those who study such things as a 'Tourney Beast'. The principle has been extended in recent times to produce Tourney Ostriches and Tourney Camels among others. Halfway between the Snap style beast and the stereotypical Hobby Horse are the traditional 'Osses of Minehead and Padstow4, the currently inactive Salisbury Hob Nob5, and many of the Irish Lair Bhan6. In these cases only the head of the wearer projects through the frame.

There is another equally dramatic animal disguise found all across Europe; the Mast Beast. In this type the head of the beast, most commonly an actual animal skull but sometimes a wooden replica, is mounted on a pole (the 'mast'). A cloth attached to the head covers both the usually bent over body of the operator and the stick which supports the head, concealing the operator and suggesting the shape of the animal. There are surviving intact Mast Beast traditions from Cheshire and Kent in England, and from South Wales. Interesting parallel traditions exist in the Nordic countries, in the form of the Yule Goat, and further afield in South Eastern Europe. Fig 1 Shows Knobbin, the Wild Oss of the Dorset Knobs Mummers, a Mumming side of which I am a proud member.

Cheshire Soulcakers

In comes Dick and all his men, we've come to see you once again. Once he was alive but now he's dead, and all that's left's this poor old head. Woah Wild Oss woah!

The village of Antrobus still continues the once widespread tradition of Soulcaking. This was in past times the practice of begging for cakes, money or beer, at Samhain, the origin of Trick or Treating. Revelers went out in disguise, either to avoid sanctions from authority, or more arcanely perhaps to impersonate the spirits of the dead. Soulcaking is just one aspect of widespread disguised visiting customs from across Europe, carried out usually at Samhain or Yule.

In Cheshire each village would in the past have had one or more teams of Soulcakers, and each would have a mast horse locally called the 'Wild Oss'. The horses were made from horse skulls which had been buried in lime and mounted on a short pole which forces the operator to bend over sharply. The jaws can open and shut, worked from under the cloth which conceals the operator. According to local tradition village teams would sometimes fight, the aim being to steal the other team’s horse skull, which if buried under an oak tree would secure good luck for the victorious village. The 'Oss would also take part in an otherwise typical Mummer's play featuring a King George and a Turkish Knight. The current Antrobus 'Oss is actually made from the skull of a donkey, covered in black painted papier mache with red glass eyes.

Kent Hoodeners

We are St Nicholas Hood'ners who come round at Christmas time,

We are just simple country folk who always talk in rhyme...

The Hooden Horse tradition of Kent uses a mast beast with a wooden head, articulated jaws worked by a string, and a bent over operator, giving a similar overall effect to the Cheshire tradition. Hooden Horses are active at Yule and are often accompanied by other folk characters such as a man-woman 'Mollie', a Groom or Waggoner, a Jockey and sundry musicians and followers. There are several very old Hooden Horses still in active use. Hoodening can still be seen around Thanet.

Mari Llwyd

Wel dyma ni'n dwad, Gy-feillion di-ni wad, I ofyn am gennad I ofyn am gennad, I ofyn am gennad i ganu.

Well here we are come, innocent friends, to ask leave to ask leave, to ask leave to sing.

South Wales has a fascinating and probably very ancient Mast Beast tradition, the Mari Lwyd7. Around New Year a gang of men including a Sergeant, a Merryman who plays the fiddle, and Punch and Judy accompany their horse, the Mari Lwyd, around local pubs. The Mari Lwyd is taller than the other British Mast Beasts, with the horse skull mounted upon a long pole so that it towers over the spectators, a long white sheet hanging down to cover the operator. Like the other Mast Beasts the jaws are articulated, and it usually has bottle bottoms for eyes.

The pub (or one assumes the household in times past) refuse the party admittance, and a poetry match ensues between those inside and the Mari's party outside. While this goes on Punch and Judy attempt to force an entry elsewhere. Apparently in the past free drinks would be given to good poets inside the pub if they could verbally keep Mari Lwyd parties at bay, because if the Mari's party won at the poetry match, or managed to force an entry, they would demand free drinks, Punch and Judy would cause havoc, and the Mari Lwyd would chase young women. These days the poetry match is largely symbolic and the Mari Lwyd's party will usually be admitted without a struggle. The Mari Lwyd can still be seen around Llantrisant and Pontyclun.

Rams Skull Beasts

Here comes me and our old lass, short o' money, short o' brass. Pay for a pint and let's all sup, then we'll show you our jolly old Tup.

On the Gower in South Wales youngsters would impersonate the actions of their elders using a ram's skull to make a kind of mock Mari Lwyd.

In Derbyshire a ram's skull or wooden replica was used, or sometimes even grislier, a ram's head complete with flesh. This would be mounted on a pole and the operator covered in sacking and possibly a sheepskin. The song The Derby Tup, (which tells of a monstrous giant ram and the use all his parts might be put to) would be sung and then the slaughter of the ram would be enacted with much horseplay, which would end with a collection. Sometimes elements from the Mummers play might be included such as a death and resurrection. The Derby Tup play is still performed in Derbyshire, though I can't find out where...

The Yule Goat

Records of Christmas guising traditions are widespread all across the Nordic countries. The Norwegian Julbukke, Swedish Julbok and Finnish Julupukku (incidentally also the Finnish name for Father Christmas) were once common, and often took the form of performers wearing goat masks, or of goat's skull type mast beasts, or a mast beast whose head was made from two bunches of straw, fashioned to resemble a goats horned head and wearing a bell around its neck. The Yule Goat would usually be accompanied by men dressed as women. These days the Yule Goat is most commonly a large decorated model goat displayed in the civic centre. In Gävle (Sweden) there is a famously large example built of straw where the civic authorities struggle every year to prevent a premature burning by local youths!

Making a Mast Beast.

First catch your horse... Actually there are several taxidermy suppliers who can supply you with a horse or ram's skull. It is also possible to purchase them through Ebay. However I recommend Emma Tenebrae at Occult Fetish. She has a sensitive attitude to the animal's spirit, and obtains her horse and ram's heads from a reputable abattoir. Of course you could obtain a horse's head yourself from a slaughterhouse or local hunt, but processing a large animal skull is too involved a topic to cover here. You might be lucky enough to find a ram’s skull in the countryside, but the lower jaws must be intact to make a good mast beast. Fig 2 shows Rambone, a ram's skull we obtained from Emma.

Inspect your skull for weak spots. Horses will have been despatched with a captive bolt pistol, and therefore there will be a hole in the crown of the skull which may need repairs. Weak spots can be reinforced with white Milliput modelling clay. Any loose teeth can be glued into place with an epoxy glue like Araldite. Once you have reinforced the skull, tie or wire the top of the skull and the bottom jaw together. It's important that they can't come apart as the pole supports only the bottom jaw. However they must also be able to move as you want the jaws to open and close. Fig 3 shows one of the leather thongs that hold Knobbin's upper and lower jaws together. Rambone's are tied with sisal twine.

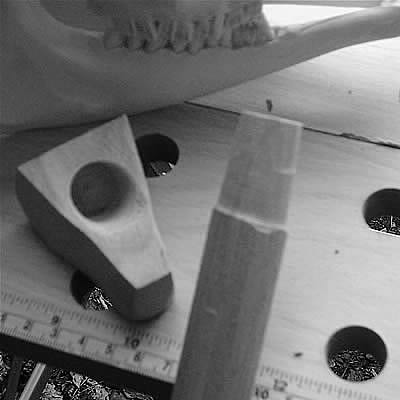

Cut a wooden block which fits snugly into the hollow between the lower jaws. This block can be built up from layers of thick plywood glued together, or from a single block of wood. Take your time removing wood slowly until the block fits tightly. The irregular shape of the jaws makes this a difficult job, but doing it well is essential to produce a durable beast.

Drill a hole through your block slightly smaller than the diameter of the stick you are going to use as your 'mast'. I recommend a piece of strong hardwood dowel, or a broomstick. A Mari-Lwyd style beast must have either a long pole, or some method of supporting a shorter pole at waist level must be devised. We found that a tin cup held round the waist by putting a belt through the handle helped support the considerable weight of the horse skull. A Forstner bit will cut a flat bottomed hole with minimum fuss, or you could use a spade bit. A drill press will make this job easier, or if you use a hand power-drill you should try to clamp the block to a workbench and have a friend help you drill at the right angle. Think about the angle you want the skull to be at in relation to the pole. You may want to drill the hole at quite an angle, especially for a Ram's skull which will look much better if it tilts forward on its mast.

Shave a little off the top of the pole with a knife or more slowly with sandpaper until it fits the hole in the block snugly. Fig 4 shows Rambone’s block and stick ready for fitting.

Try the skull, block and pole in position to make sure you are happy before you glue anything permanently into place. Then, using a two part epoxy glue like Araldite, glue the block into place in the lower jaw. Once it has set push more epoxy into any gaps from one side with a spatula. When this second lot of epoxy has dried, turn the jaw over and fill up any gaps from the other side. Finally fill remaining gaps with milliput, as in fig 5.

Push the pole into place. Now you must work out a mechanism for opening the jaws. The bottom jaw is fixed to the pole so it is actually the top jaw that moves. Luckily animal skulls are finely balanced and move easily. We found with the horse and ram’s skulls that a wooden rod tied in to the back of the top jaw worked well. See figs 6 which shows Rambone's rod and fig 7 which shows a naked Knobbin operated by my partner Kate.

Now the cloth, which would traditionally be sacking for the smaller beasts, must be tied into place. We tied it around the back of the horse skull where there is a natural bulge, this keeps the cloth in place. Rambone's skull is not large enough to tie the cloth to, so the cloth is tied around the top of the pole below the skull. This meant that the rod which moves the jaws had to be fed through a hole in the cloth. To hide this rod and to mask the back of the skull we tied a second piece of cloth to the first behind the skull. The cloth is then sewn shut in front of the pole with blanket stitch. Make sure there is room under the cloth for the operator, and that it is long enough to conceal their legs, without being so long as to trip them up. If you are making a Mari-Lwyd style mast horse, then obviously the cloth must be much longer, a large bed sheet being the traditional covering. You will have to experiment with the cloth to work out a way to attach it which covers the operator without obstructing the jaw mechanism.

We have decorated our horse with horse brasses, and our ram with a cowbell. The ‘Oss also sports a mane made of old rope and a tail made from, well, a horsetail... Use your imagination! You can find photographs of decorated ‘Oss's on the Master Mummer's and Folk Drama Research Group website. Fig 8 shows the completed Rambone, ready to grace a Samhain or Midwinter procession. We hope you have as much fun with yours!

Notes

1 The now sadly disappeared Dorset Ooser was the property of a family in Crewkerne, Dorset.

2 Norwich has had a dragon since before 1420. Many medieval Guilds had giants or beasts which they used in processions. Some incarnations of Snap could open and close their wings as well as breathe smoke and fire.

3 The Horn Dance features six dancers bearing antlers, a Hobby Horse, a Boy with bow and arrow, a Fool and a Maid Marian.

4 Both Padstow and Minehead have flourishing May celebrations, central to which are their 'Osses.

5 Hob Nob and his Giant companion are in Salisbury museum. They were used in civic processions until the beginning of the twentieth century.

6 The Lair Bhan (White Mare) appears as part of the Christmas visiting and parading traditions of the Wren Boys, most commonly in County Kerry. They may also have been used at Beltaine in the past.

7 Literally 'Grey Mare' from Llwyd, Welsh: Grey, and Mari, derived from English: Mare.

Bibliography

Books:

English Ritual Drama, Cawte, Helm, Peacock.

Ritual Animal Disguise, EC Cawte.

The Hobby Horse and other Animal Masks, Violet Alford.

Crossing the Borderlines, Nigel Pennick.

Chronicle of Celtic Folk Customs, Brian Day.

Video:

Archive films of Padstow, Minehead and Antrobus traditions, supplied by FolkTrax..

Mummers and Masks, a film made for Canadian Television by Peter Blow.

Websites:

Master Mummers: http://www.mastermummers.org

Traditional Drama Research Group: http://www.folkplay.info

Hoodening: http://www.japanesetranslations.co.uk/hooden/hoodening.htm

Dorset Knobs: http://www.dorsetknobs.co.uk

Corwen ap Broch is a musical instrument maker and musician. He performs and runs workshops with his partner Kate Fletcher. They are also both members of the Dorset Knobs Mummers. See www.ancientmusic.co.uk for details of instruments, recordings, workshops and performances.

Back to Articles Home